For years, my colleagues in the European Parliament and I worked on the EU copyright reform – on improving the Commission’s original proposal, but above all, on preventing the worst. More than 5,000,000 signatures made the petition against Article 13 the biggest in EU history. Many activists invested their time and passion into the fight. By taking to the streets, 200,000 protesters ensured that our concerns became impossible to ignore.

And yet despite all that, the reform passed: Upload filters and the “link tax” are coming. What remains of our efforts?

Photo: (cc) by-nc-sa Tim Lüddemann • Protester: Emuolia Star

Photo: (cc) by-nc-sa Tim Lüddemann • Protester: Emuolia StarProtest achievements

Because the interests of civil society were neglected in the legislative process, the people of Europe had no choice but to make themselves heard with e-mails, petitions and protests – and that’s what they did.

In July 2018, the movement secured its first victory: MEPs denied rubber-stamping the position of the responsible committee, which is usually just a formality. Instead, they demanded improvements – clearly impressed by the amount of public interest. At that time, the petition was just closing in on 1 million signatures.

Unfortunately, MEPs subsequently fell for dirty tricks: Axel Voss presented a text as a “compromise” in which he had only cosmetically removed references to upload filters, while still requiring them. At the same time, the pro lobby successfully spread the rumour that the protest was merely staged by big US corporations: The birth of the infamous legend of the “bots”. These tricks were so successful that the Parliament green-lighted the barely changed text in September.

Between September 2018 and March 2019, the protest movement managed to reduce the approval of the law among MEPs by almost 10 percentage points (from 62% to 53%). This late in the legislative process, this is remarkable. In the end, we came only a few votes short of holding another vote on striking Article 13 from the Directive. Though we kept our hopes up, making such a radical change at the last possible moment would have been unprecedented.

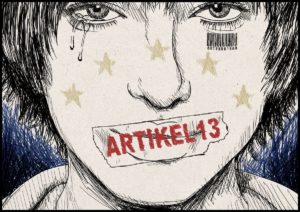

Massive streets protests, especially in Germany, succeeded in making a topic as arcane as copyright law an issue that was hotly debated everywhere from schoolyards to the highest levels of politics. Many creatives – who we were told were supposed to benefit from Article 13 – instead applied their skills to fighting it, creating protest songs and graphics.

A novel alliance of digital rights NGOs, political parties and social media personalities succeeded in politicising and mobilising an entire generation of digital natives. Countless people rose to new challenges: Entertainment YouTubers suddenly found themselves in the role of reporters or political commentators, internet users became activists and organisers, and many participated in the first protests of their lives. These experiences will leave a lasting impact.

The protest was so effective that it compelled both parties in the German government to declare that they would at least mitigate some of the problems in the national implementation of the law. A misguided idea for a Directive that was intended to establish a “digital single market” – that is, to harmonize national laws. Nevertheless, it’s an admission of how well-founded our criticisms were, and an affirmation of how far we have come: Thanks of our efforts, nobody can afford to take political responsibility for upload filters any longer. The initial arrogance of conservative MEPs has been replaced by sheepish concessions – or lip service, at least.

* * *

Improvements to the text

In the negotiations in Parliament, my team and I were able to make progress on a number of issues:

- Fewer upload filters: We managed to restrict the infamous Article 17 (formerly 13) to for-profit platforms: This was not the case in the Parliament version of July 2018. The restriction to services which “play an important role on the online content market by competing with other online content services, such as online audio and video streaming services, for the same audiences” was also our doing, even though it unfortunately only made it into a recital, rather than the article itself.

- Fair remuneration: Even though the text didn’t end up banning so-called “total buyout contracts”, Article 18 does establish fair remuneration of artists as a fundamental principle for the first time at the EU level. The Commission had had no such plans. In doing so, the Directive meets one of the demands from my 2014 copyright report.

- Publisher/label transparency: Article 19 requires transparency from distributors, such as publishers and labels, towards the creatives whose works they exploit. In trilogue we managed to ensure that this doesn’t only happen on demand, but in the form of regular reports.

- What is free must remain so: The Directive clarifies in Article 14 that the mere digitization of a work whose copyright has already expired can not fall under copyright anew. This allows platforms such as Wikipedia to publish photos of older artworks without having to worry about licensing. This stems from an amendment I filed, and was already proposed in the Reda Report.

- Out-of-commerce works available: Cultural institutions like museums and libraries across Europe will be allowed to put works online which are no longer commercially available, independent of their copyright status (Article 8). In the negotiations, we were able to remove several restrictions to this right that the Commission had been planning.

- Minimum standards rather than leveling down: For all new copyright exceptions and limitations that the Directive establishes at the EU level, the principle will apply that member states which already have further-reaching exceptions in national law may keep them. This provision (Article 25) was inserted at our request at the last moment, in trilogue.

- Parody allowed everywhere: Article 17, paragraph 7 states that uploaders must be able to rely on a copyright exception for caricature and parody in every member state. Since such an exception doesn’t yet exist everywhere, this fulfills the demand from the Reda Report to make it mandatory across Europe.

* * *

Moving forward

Member states now have two years to implement the reform into national law. The wording of the Directive does leave some leeway – for example, in the specific interpretation of what constitutes a “large amount” of user uploads, and thus how many platforms fall under the scope of Article 17 (formerly 13).

The publishers’ lobby will without doubt advocate for the strictest possible interpretations of the Directive – civil society must resist, and we must do this in all member states. So please stay involved – or at least support NGOs like EDRi and Epicenter.works, who will continue lobbying for our rights. SaveTheInternet.info, the activists who started the petition, have also announced that they will keep working on the subject.

Meanwhile, we will keep pushing for real copyright reform: After all, this “reform” still leaves copyright law fragmented across Europe and in dire need of an update. The demands loudly expressed by thousands of users in the consultation from 2013 remain unfulfilled. For one, we still urgently need a copyright exception for today’s internet and remix culture. Our efforts must continue.

My message to all who took part in this movement: Be proud of how far we came together! We’ve proven that organised citizens can make an impact – even if we didn’t manage to kill the whole bill in the end. So don’t despair! Stay politically active, and definitely go vote in the European elections at the end of May!

To the extent possible under law, the creator has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this work.